Hito Steyerl. Factory of the Sun

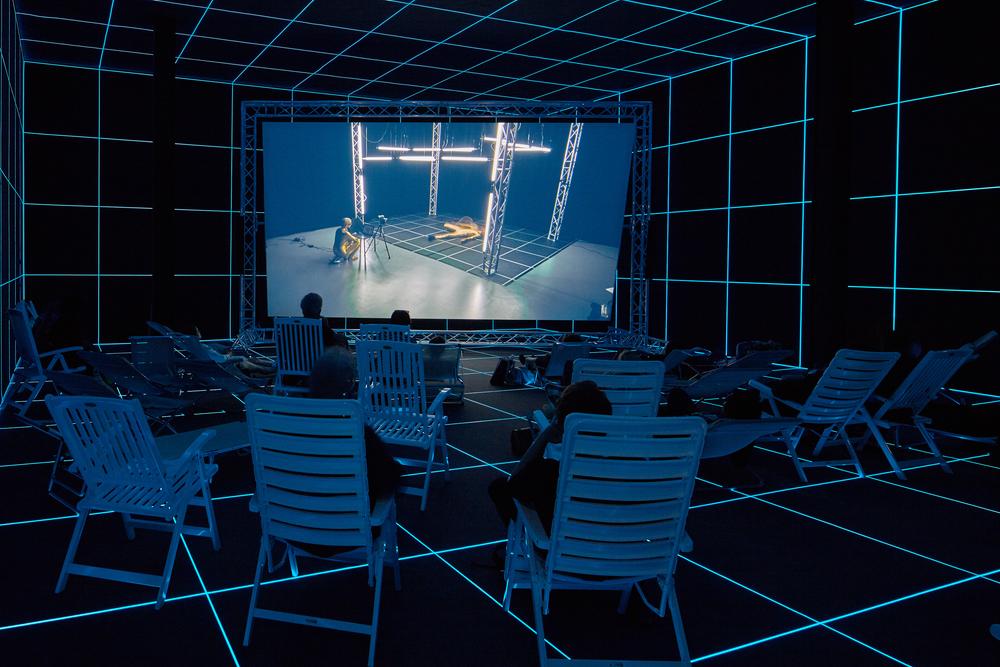

Hito Steyerl’s futuristic films are based on the strangeness of contemporary life: “Real biographies are so much more interesting than anything I can imagine,” says the artist, who studied documentary filmmaking.1 Screened in an immersive grid of glowing blue LED lights—a kind of Star Trekkian “holodeck” able to materialize a different world in three dimensions2—Factory of the Sun (2015) tells the story of workers whose forced dance moves in a motion-capture studio are turned into artificial sunshine. The surreal story is loosely based on an actual YouTube phenomenon— homemade dance videos made by Steyerl’s studio assistant’s brother went viral and were then used as a model for Japanese anime characters—and a news story about an experiment at CERN nuclear research facility in Geneva that claimed to have measured a particle traveling faster than the speed of light.3 On screen, Steyerl rendered such a reality through “images and avatars”4 using a montage of YouTube dance videos, drone surveillance footage, video game characters, fictitious news, and real documentation of recent international student uprisings. Modern warfare, corporate culture, and anti-capitalist resistance movements are played out by disembodied characters—avatars, bots, or proxies for human viewers who watch the video from the vantage of reclining beach chairs.

Hito Steyerl, in “What Is Contemporary: A Conversation with Hito Steyerl,” conversation with Lanka Tatersall, MOCA Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, February 21, 2016, available at youtube.com/watch?time_continue=13&v=sNW1PP-034Q&feature=emb_title. ↩︎

Hito Steyerl, in “What Is Contemporary: A Conversation with Hito Steyerl,” conversation with Lanka Tatersall, MOCA Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, February 21, 2016, available at youtube.com/watch?time_continue=13&v=sNW1PP-034Q&feature=emb_title. ↩︎

Hito Steyerl, in “What Is Contemporary: A Conversation with Hito Steyerl,” conversation with Lanka Tatersall, MOCA Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, February 21, 2016, available at youtube.com/watch?time_continue=13&v=sNW1PP-034Q&feature=emb_title. ↩︎

Nicolas Linnert, “All Access Politics: Reality and Spectatorship in Two Film Installations by Jean-Luc Godard and Hito Steyerl,” X-TRA 19, no. 3 (Spring 2017), available at x-traonline.org/article/all-access-politics-reality-and-spectatorship-in-two-film-installations-by-jean-luc-godard-and-hito-steyerl/. ↩︎