We traveled, ending up on Guam . . . where we began to make maps for the navy. . . . We were making photomosaics and also interpolating and making maps from aerial photographs, something we had been trained to do. . . . This, of course, gave me a new viewpoint for looking at the world—the aerial view. And when I looked through the Stereo-Comparagraph, a machine that aided you in picking up contours from the photographs, what I really saw were marvelous abstract patterns.

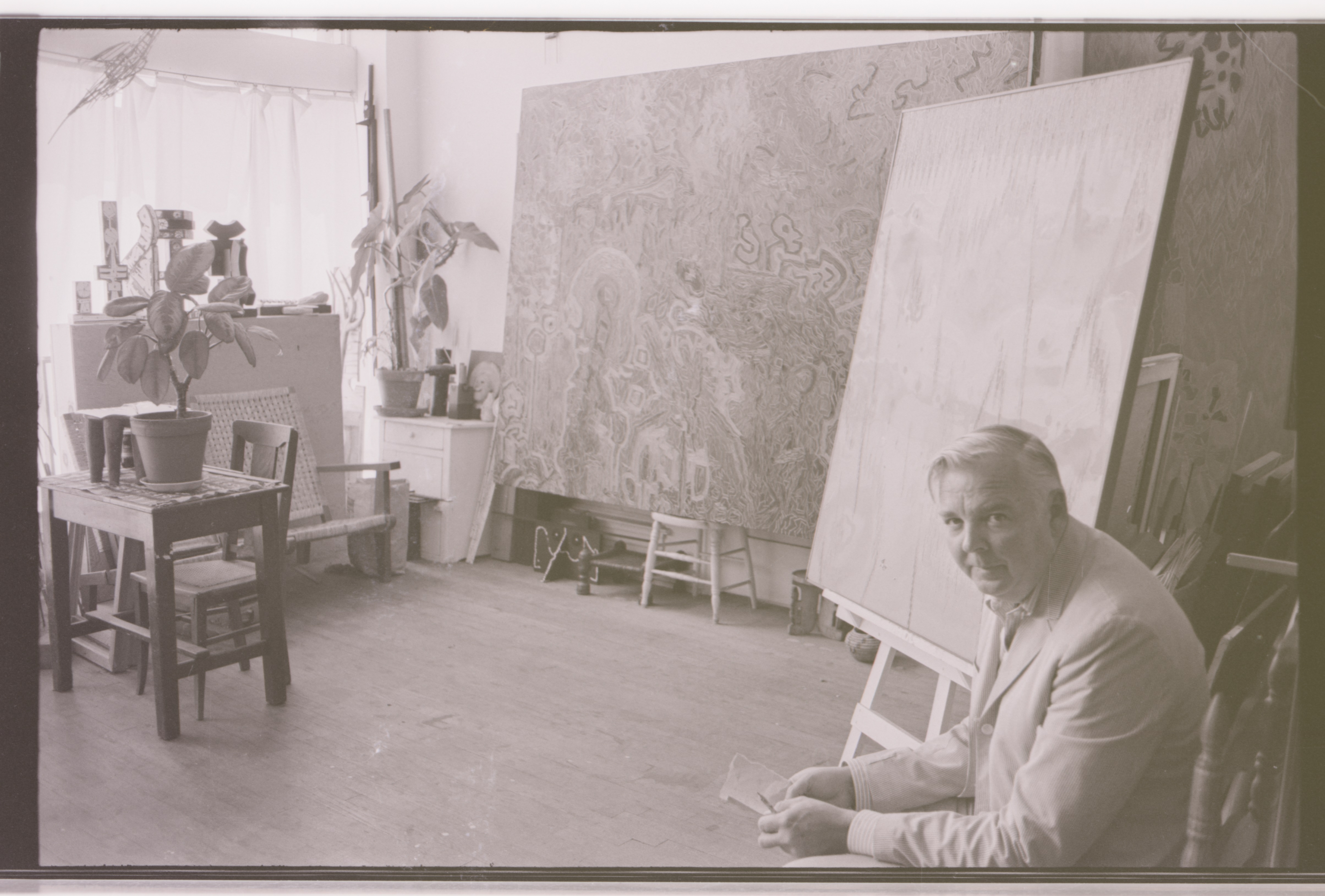

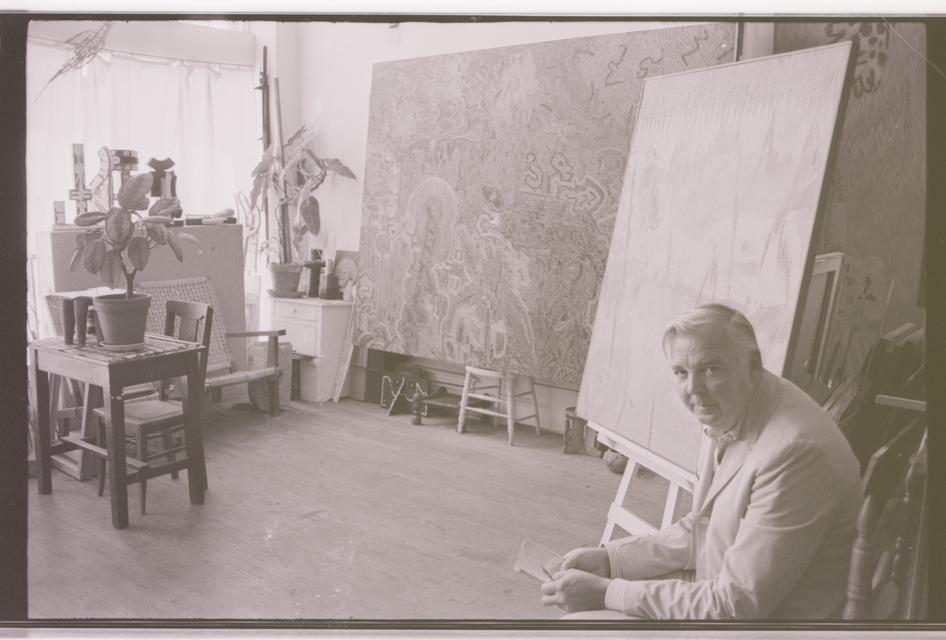

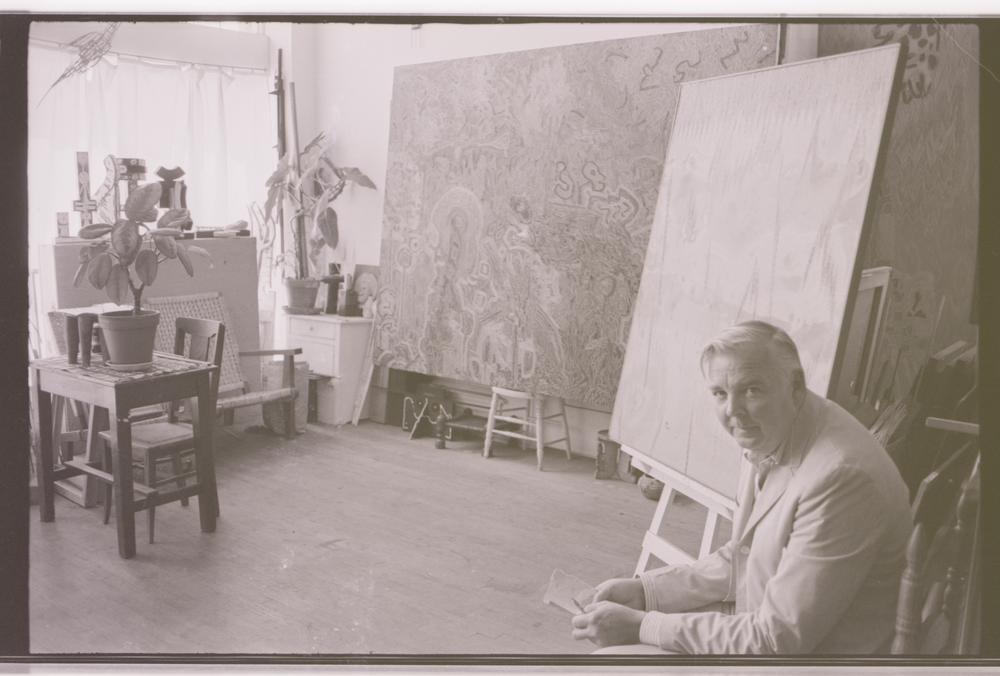

Lee Mullican

United States, 1919–1998

A Son of Oklahoma Pioneers

Lee Mullican was born in 1919 in Chickasha, Oklahoma, a small farming town in the then-newly incorporated state. Mullican began making art at a young age—his mother was an amateur artist—and he recalled being particularly struck by images in a catalog his parents brought back from the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair: “There was a Chagall, Picasso, and other things that I had never seen before. . . . I knew that that’s where I wanted to go. Even at that age I was not interested in just setting up a still life of flowers and working from it. . . . All this strangeness intrigued me. . . . I had entered a modern age.”1 Mullican was drafted into the Army in 1942, serving three years as a topographer in the Army Corps of Engineers. Though it was a difficult time—“a torture”2—his experiences in the Army expanded his world: he visited museums in Washington, DC; Baltimore; and New York while stationed at Fort Belvoir, Virginia, and met lifelong friend Jack Stauffacher, a printer from San Francisco.3 “He was a printer and was in the printing company of the battalion. We printed our own maps. I ran across this fellow one day, sitting on the toilet, reading the Life of Buddha. So, I said, here is someone that I must get to know.”4

Lee Mullican, oral history interview with Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, May 22, 1992–March 4, 1993, transcript available at aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-lee-mullican-12846. ↩︎

Lee Mullican, oral history interview with Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, May 22, 1992–March 4, 1993, transcript available at aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-lee-mullican-12846. ↩︎

Lee Mullican, oral history interview with Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, May 22, 1992–March 4, 1993, transcript available at aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-lee-mullican-12846. ↩︎

Lee Mullican, oral history interview with Joann Phillips for the Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles, as part of “Los Angeles Art Community: Group Portrait,” January 8, 16, and 23 and February 20, 1976, transcript available at archive.org/details/leemullicanoralh00mull/page/n349/mode/2up. ↩︎

Surrealism for the New World

At the urging of his army friend Jack Stauffacher, Lee Mullican moved to San Francisco in 1947 and met surrealist artists Gordon Onslow Ford and Wolfgang Paalen. The two had just come from Mexico City, where they had been living to escape the war in Europe. Mullican had come across Paalen’s art journal DYN during the war and was fascinated by its images of Native American art. After meeting in Northern California, Mullican studied Paalen’s collection of Pacific Northwest and pre-Columbian indigenous objects and the artworks in Onslow Ford’s studio by European surrealists like Max Ernst and Paul Klee.1 These influences majorly shaped Mullican’s stylistic and theoretical development during a period when he felt himself “searching, fighting for a refinement of work and ideas.”2 Together, Paalen, Onslow Ford, and Mullican formed the Dynaton—a short-lived but significant collective that culminated in a groundbreaking group exhibition called Dynaton at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1951. During a period of postwar optimism, the Dynaton shared a philosophical approach to artmaking as a mode of boundless exploration; like scientific inquiry, art could open new frontiers. The artists used approaches like automatism, or the practice of creating art by tapping into the unconscious, to access realms of thought uninhibited by the rational mind.

Lee Mullican, oral history interview with Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, May 22, 1992–March 4, 1993, transcript available at aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-lee-mullican-12846. ↩︎

Mullican, “Thoughts on the Dynaton,” in DYNATION Re-Viewed (San Francisco: Gallery Paule Anglim, 1977), 4. ↩︎

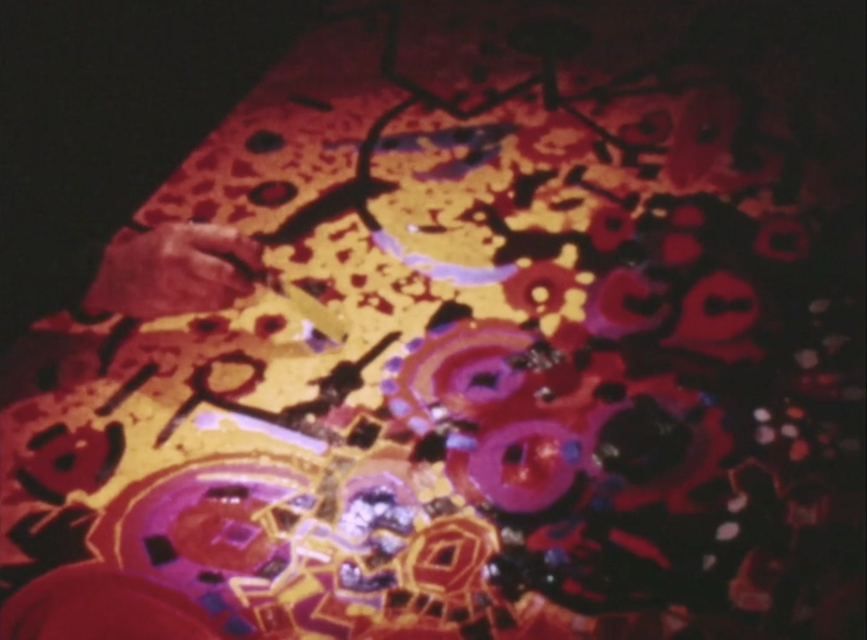

This Marvelous Tool

When Lee Mullican found himself one day without a paintbrush, he reached instead for a printer’s knife. At the time he was staying with Jack Stauffacher, a printer Mullican had met while in the Army who ran the Greenwood Press in San Francisco. Borrowing Stauffacher’s “marvelous tool”1—a knife with a flexible blade used to apply ink to rollers—Mullican developed a distinguished approach to markmaking by adapting the blade’s square tip to apply and score paint, creating abstract forms from linear dashes that resemble geometric glyphs or stitches in textiles.

Jack Stauffacher, in Lee Mullican: Paintings 1952–1968 (San Francisco: John Berggruen Gallery, 2007), 4. ↩︎

Woven Surfaces

Lee Mullican realized early in his career that his signature painting style created surfaces that resemble woven objects. When he came across a Pomo Native American basket at a San Francisco antique shop, the artist recognized the slightly three-dimensional, parallel marks: “The kind of feathered surface of the basket was a little bit like what I was doing in painting.”1 Though his technique remained the same, the conflict he felt between abstraction and image was a constant challenge. In Nightshade (1958), a work made after the artist moved from San Francisco to Los Angeles, images seem to emerge from a palette quieter than in most of the artist’s other works. “It was at this time that I began to realize that I didn’t need to be quite such a purist—or quite that abstract. . . . I began to employ certain aspects of heads and bodies and invented animal forms.”2

Lee Mullican, oral history interview with Paul Karlstrom for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, May 22, 1992–March 4, 1993, transcript available at aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-lee-mullican-12846. ↩︎

Lee Mullican, oral history interview with Joann Phillips for the Oral History Program, University of California, Los Angeles, as part of “Los Angeles Art Community: Group Portrait,” January 8, 16, and 23 and February 20, 1976. Transcript available at archive.org/details/leemullicanoralh00mull/page/n349/mode/2up. ↩︎