Mona Hatoum. Political Performance

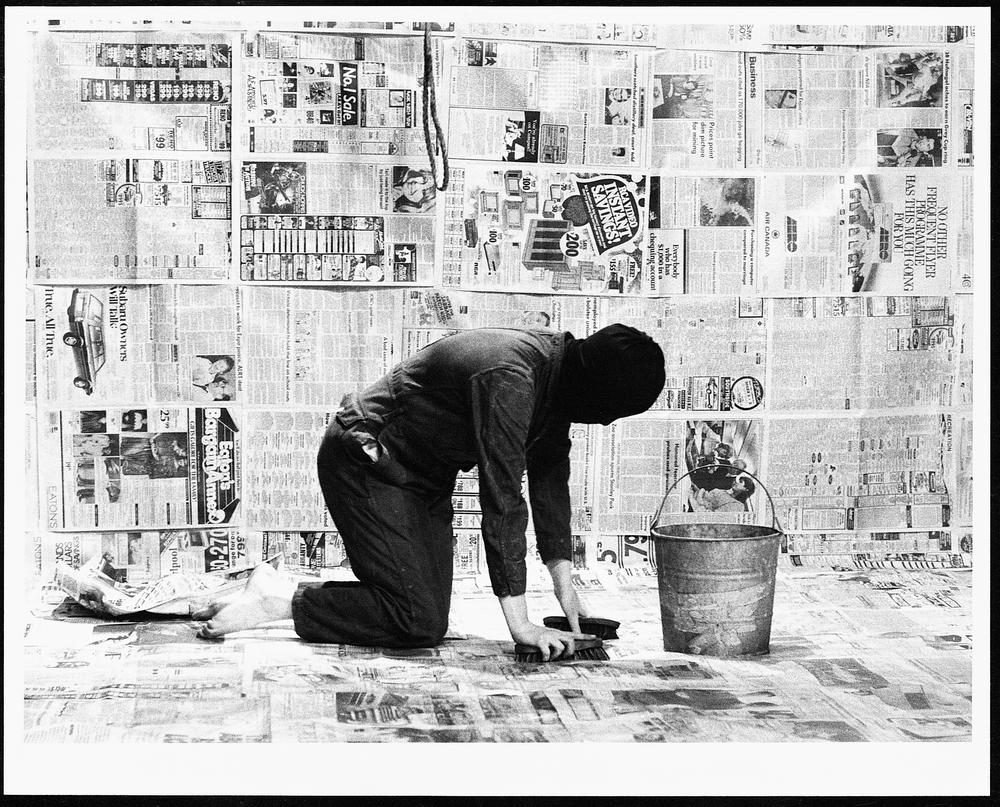

Mona Hatoum was born in Beirut, where her Palestinian parents settled after being exiled during the Arab-Israeli War in 1948. In 1975, while on a short trip to London, the Lebanese Civil War broke out and prevented her return home. She remained in London, and between 1975 and 1981 she studied art at Byam Shaw School of Art and Slade School of Fine Art.1 “The Slade politicized me,” said the artist. “I got involved in feminist groups . . . started examining power structures and trying to understand why I felt so ‘out of place.’”2 Ideas around instability and displacement appeared early in Hatoum’s experimental, even dangerous work, like running 240 volts of electricity through a circuit of metal household objects, and she began making temporary performance works too hazardous for galleries. In Variation on Discord and Divisions (1984), the artist crawled onto a stage covered in sheets of newspaper to scrub the floor with a bucket of red-stained water. In a series of vignettes, she cuts holes through an opaque hood masking her face with a knife; sets a dining table and pulls raw kidney from under her clothes, cutting it up and serving it to the audience on plates, and later projected slides of newspaper articles reading “35,000 people have been the victims of death squads since 1980. 1,500 people have been butchered in cold blood in Nazi-like fashion. . . . Twin refugee camps. . . Oppressed people. Famine worse than ever.” Like the sculptural work that followed, the scene was deeply sinister and placed the body in a vulnerable relationship with the home and the state—with cultural, historical, and economic forces.